Soil! Water! Seeds! Photosynthesis!

Man Ray bred dust. Perhaps he cross-pollinated it on his visits to Lee Miller and Roland Penrose at Farley Farm, Sussex, where the legendary Surrealist couple tended their vegetables, bulls and sculptures, delighting other guests such as Max Ernst, Picasso, Leonora Carrington and Joan Miro.

All farming practices are purposeful. Each has its unique beauty. For better or for worse, each ingrains the earth and language itself. Farming, alongside the gloriously sequestered art of forestry, is Interactive Environmental Sculpture and : winnow the oats from the chaff, delve for turnips, reap hay, forage for berries and fill panniers with truffles snuffled by erudite Tuscan swine! Cut the turf of a peat bog, perform falconry in fallowfields! Wheelwrights, Apiculturists, Blentonists, Meadowers! Thatch granaries and dovecotes, platch ryegrass, devilsmilk, wartweed and dandelions to adorn windmills and watermills! Scythe sorrel leaves and mistletoe. Night-farmers, archaic emptiers of urban cesspits, light your haw-haw lanterns that we might dream of the rake-assisted causology of olives raining from Catalonian branches, of honey-gathering under a halo of lilac clouds, of harvesting Thai elephant dung because this is the primary ingredient of Black Ivory Coffee. What pleasures abound in the clotting of cream, the herding of alpacas, the shelling of almonds, the weaving of willows, the pressing of ice-grapes, from share-cropping to collectivism to aquaponics!

And in these fruitful, celestially-nomed activities lies the purpose and aesthetic of our garments: our hydropolous bibs and braces, our clogs and sandals and smocks, our nettleproof twill pantaloons, bonnet of Dutch straw and Provençal neckerchiefs spotted with cicadas; our rubber galoshes or stout orchard boots, coolie hats, sou-westers, lederhosen, barbour jackets, amish beards, dirndl skirts, sporrans and gingham blouses. Sarafans, chemises, ponevas and plakhtas, kokoshniks and never forget: the further east the wider the cummerbund!

Take Le Farming Times to a tree, recline thereunder, and immerse thyself within, perchance to dream of farming.

TOLSTOY AND HIS FABULOUS SMOCK

As you probably recall, Tolstoy’s passion for the psychologically restorative activity of mowing a meadow is embodied most clearly in Anna Karenina, when Levin, spurned by Kitty, escapes to his country seat, picks up his scythe and joins his army of serfs for a day. He swings his scythe repeatedly, under a fulsome Russian sun, mesmerically cutting row after row in the company of people who are essentially his slaves, but who do not appear to resent him. And when they are all exhausted, they lie back together in the hay and talk about love. Thus Levin regains peace of mind. Tolstoy does not tell us what Levin is wearing, but it is highly likely that a peasant smock would have been in order.

Lev Tolstoy wears such a garment in practically all of his later portraits. He was even clad in one while having his final fateful argument with Sofia, his wife, before fleeing his idyllic ancestral estate Yasnaya Polyana on a wintry night in late October 1910. Thence he wandered for three fitful weeks until, beset by pneumonia and eerie petulance, he died in the tiny rail station of Astapovo. He was 82

The smock that launched a multitude of ploughs

Many Tolstoy-inspired farming communities endure even today, from Alaska all the way around the globe to Siberia (including one in the Ukraine whose members wear white druid-style robes while their leader presents himself as the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, and two rather more subdued farming settlements in England, lacking in any specific dress code). Tolstoy declared himself somewhat ambivalent about people taking inspiration from his specific personality, though he did express “great joy” that so many groups were practicing the principles of simple, self-sufficient living, vegetarianism and pacifism. He also obliged Sofia to welcome and host any and every disciple who came knocking at the splendid gates of Yasnaya Polyana. He deeply admired “Anatomy of Misery”, the economic treatise penned by a certain John Coleman Kenworthy, a former businessman who co-founded the Tolstoyan rural community in Purleigh, England. “It is impossible to fight the System with its own weapons,” despaired Kenworthy, “one cannot touch pitch without being defiled.” This unhappy thinker concluded that personal transformation offered the only escape from auto-created bureaucratic hades. Yet even with such guidance and despite Tolstoy’s initial support, the Purleigh community floundered and, by 1904, its few remaining citizens had abandoned the site. Kenworthy later suffered extreme psychological distress and was admitted to an asylum.

We do not know whether Max Ernst was channeling Tolstoy when he conceived his alter ego: Loplop, a bird. We can only imagine what Tolstoy would have made of Sedona, the Arizona landscape, where Ernst handbuilt his own nest among the monumental red sandstone crags, eventually hosting Henri Cartier Bresson and Yves Tanguy – who would begin his own agricultural career with Kay Sage at Woodbury Farm, Connecticut. What we can observe is the phenomenon of humans who reach to the land for solace, for nurture, and for inspiration.

Land met dreams when the melting rocks around Figueres, Catalonia, found their way into Salvador Dali’s aggrieved landscapes, which in turn inspired the Bolivian State to name one of its actual deserts after him. André Bréton returned time after time to the Desert du Retz in Chambourcy, just north of Paris, a landscape carved with dreams by François Racine de Monville and stuffed, in its eighteenth-century heyday, with follies, including the “colonne brisée”, a giant, half-shattered column stump, an ice-house in the form of a pyramid and a Mongol island encampment. Bréton was also a grand experimenter in the wardrobe department – note his fantastically nihilist headdresses and gender-fluid personae. No doubt he would have loved to pick hemp with the 21st century Sisters of Central Valley, California, garbed in a nun’s habit made of old pillowcases.

своя рубашка ближе к телу

Tolstoy is revered for his monumental novels rather than for his smock. The Russian proverb “Svoya rubashka blizhe ko tyelu” (one’s own smock is closer to one’s body) ostensibly refers to charity beginning at home, but illustrates just how deeply the peasant smock is rooted within the Russian psyche. Tolstoy’s principal pet characters, aristos every one, are at their happiest when communing with peasants (Natasha’s frenetically instinctive dance after the wolf hunt in War and Peace, Levin mowing said meadow in AK, Pierre befriended by a wise old dyedushka with a lavender dog whilst in Napoleonic captivity, W&P… to name but a few).

The reasoning seems to be that folks who work the land are morally unpolluted, wiser and less worldly than non-farmers – for the most part. Qualities that one might acquire by aping rustic fashion. The notion is over-romanticised, sure, even absurd. But given the choice, would you entrust your wallet to a politician or to an olive-farmer for safekeeping? In Tolstoy’s efforts to emulate peasants, he sought moral salvation, whilst also attending to his own comfort.

Cement Basset Hound

He guards the mill of God Saucepan Town

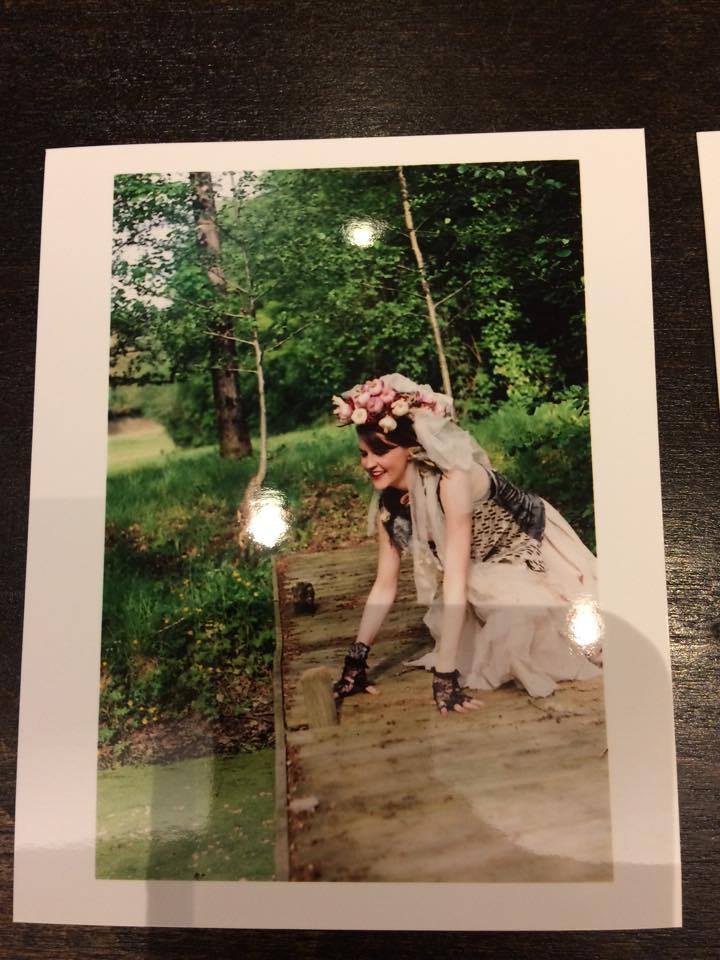

“Thank you to Reine Bonnie Melvin, our esteemed hostess, to Guy and Sophie Bachelet the marvellous mill owners, to the Bucolic Muses Liv Monaghan, Leah Bachelet and Celine Jans, and to the amazing Jean-Baptiste Rivet, photographer extraordinaire ”